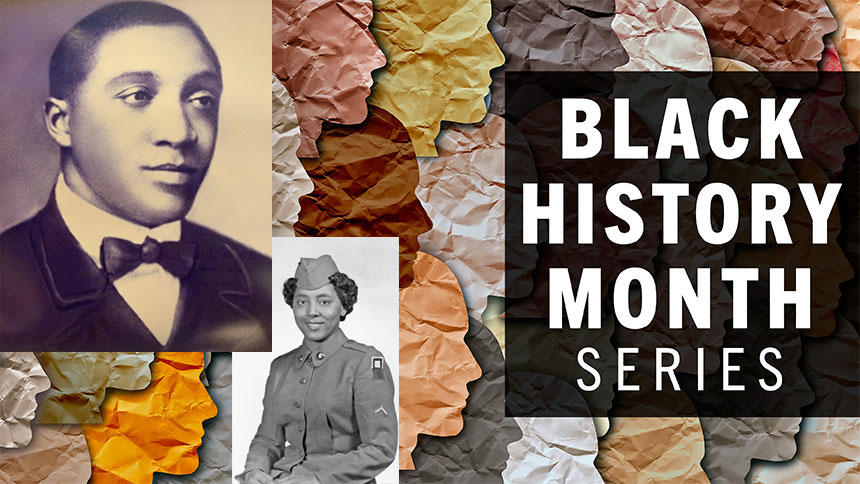

Above: David Artis Keys; Private Sarah Keys, circa 1952, Women’s Memorial Foundation Register

From early abolitionists to being the first in many states to integrate parishes and schools, the Catholic church has often been on the forefront of Civil Rights issues. The example of Jesus Christ demands that we treat all people with love, respect and dignity. However, we still have a long way to go to ensure that all of our brothers and sisters, who we know are equal in the eyes of God, are also equal in society. With that in mind, the Diocese of Raleigh presents important stories and histories of African Americans who have made incredible contributions to society. These pioneers and leaders not only overcame incredible odds to accomplish what they did in their time, but they created innovations and made impacts that are still used and felt today.

David Artis Keys was born in Washington, N.C., on September 22, 1896 — 28 years before the Diocese of Raleigh was established.

He left home to attend high school in Washington, D.C., and soon after joined the Navy. He served for several years aboard the USS Constitution, also known as Old Ironsides. It was during his Navy years that he converted to Catholicism.

After his discharge, he returned to Washington, N.C., and became active in the Black Catholic community.

The Diocese of Raleigh was established in 1924 by Pope Pius XI. At the time, the diocese covered the entire state of North Carolina, with a Catholic population of 6,000.

In 1927, David Artis Keys, Sr., married Curley Vivian Wooten and later had seven children: Marie, Sarah, David, Elijah, Cornelia, Angela and William.

During that time and for a total of 63 years, there was no physical church building because it had been burned down with much of the town during the Civil War. Black and white Catholics worshipped in private homes, empty buildings in the downtown area and even chapel railroad cars were used for the celebration of the sacraments and gatherings of the faithful.

David was a pioneer in farming and masonry and often traveled to New Bern. On a trip, he reportedly asked a priest, “What can be done for my people in Washington?” His question showed a desire of the people of Washington to reconstruct an actual church building. So, in 1927, David helped build Mother of Mercy School, with the original one-story structure being completed in three months.

The school was staffed by the Sister Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of Scranton, Penn., with the mission to teach the children of freed slaves.

The school was very successful and became the first accredited high school educating children of Black slaves. Students often traveled throughout NC, winning academic competitions. Possibly the school’s most famous student was David and Curley’s daughter Sarah Louise Keys. She is best known for taking a stand for civil rights.

In 1952, before Rosa Parks, Sarah Keys, a Black Women’s Army Corp private, was traveling on a bus from Fort Dix, N.J., to visit her family in Washington. On a stop in Roanoke Rapids, N.C., she was asked to give up her seat to a white Marine. She declined and was arrested for disorderly conduct.

Shocked to hear the story of why Sarah was so late getting home, her father, David Artis Keys, advised her to take legal action. Her father was a great support in her pursuit to seek justice. She lost the case and was convicted of disorderly conduct.

Further persuaded by her father, she continued to fight with the help of the NAACP and three years later won the court case of Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company. It became illegal to segregate Black passengers in buses traveling across state lines. A few weeks after Sarah won her case, Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat in Montgomery, Ala.

This year, Mother of Mercy Church is celebrating 200 years in Washington, and it is the 68th anniversary of Sarah Keys’ arrest.

In Roanoke Rapids on August 1, 2020, one day before the 68th anniversary of Sarah Keys’ arrest, a plaza with eight chronological murals and two bronze plaques was unveiled in her honor. The project was funded by a Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation Inclusive Public Art grant. Learn more about Sarah Keys Evans and take a virtual tour of the plaza in her honor.

Mrs. Evans is in her 90s and lives in Brooklyn, N.Y.